On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the Atomic Bomb on the citizens of Hiroshima, Japan.

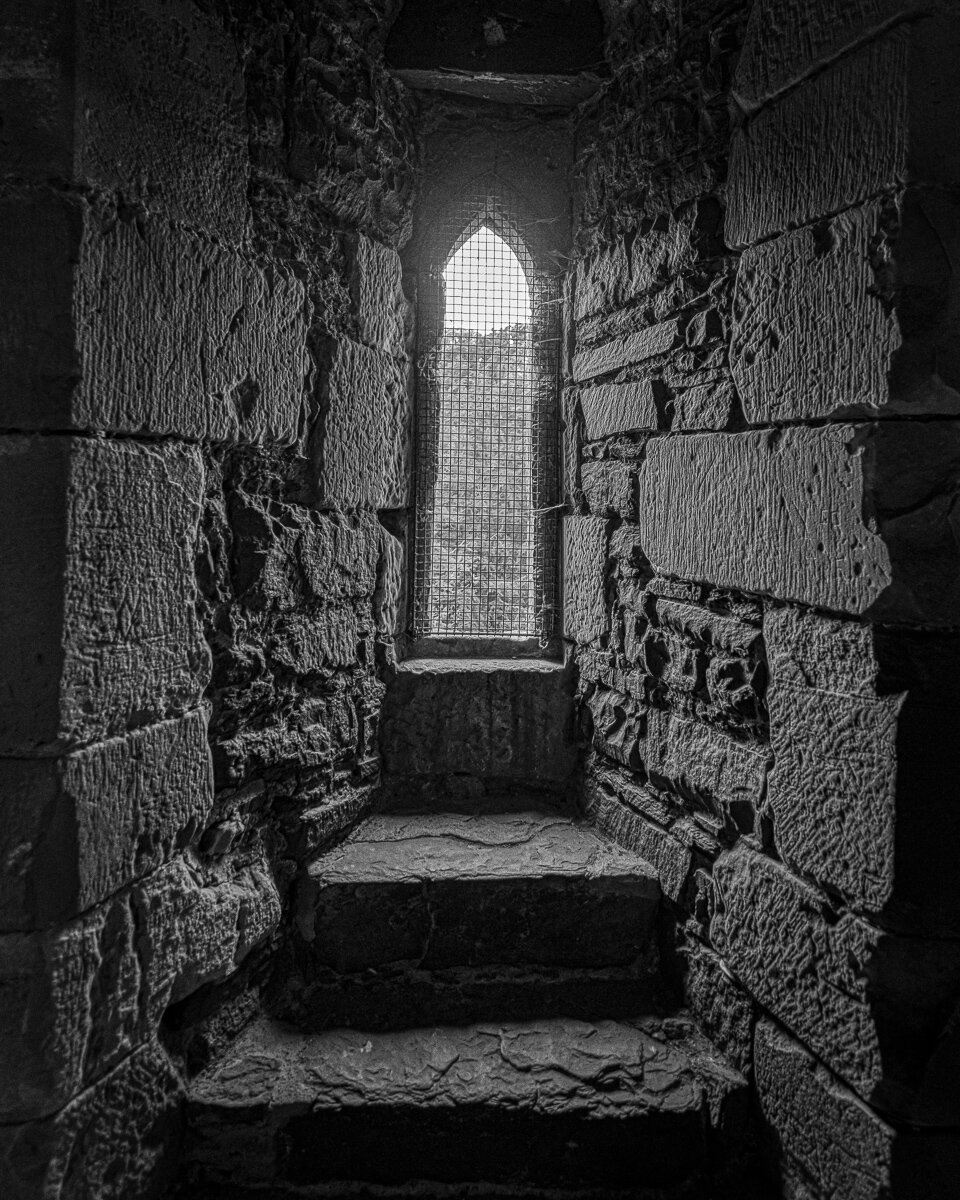

The image above is part of a wall in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The city was founded in 1589 on the Ota River delta. The branches of the delta run through the city to the ocean bay. In the picture above on the left side, you can see the Motoyasu bridge across one of the river branches. That was the target the bombardier sited, and the bomb detonated just above the building about 130 meters away that you on the right of the image. As the blast went out, that bridge directly below was spared.

A few months ago, I posted images from the island of Miyahima which is across the bay from Hiroshima. The ferry boat that takes you to the beautiful, peaceful, holy island docks next to the bridge. You stand next to two to of the pillars that survived the blast. I rested my hand on the pillar, and my heart and eyes were filled.

Motoyasu Bridge pillars

In my freshman year of college, I had a small seminar class for my history major. The focus was to study primary documents to understand and analyze historic events. The class was called The Decision to Drop the Bomb, and the documents studied had just been declassified by the Defense Department from the War that had ended barely over thirty years before. The topic has fascinated and disturbed me since.

Just a few months before, I visited the Trinity Site in New Mexico where the first atomic bomb was tested on July 16, 1945. The Army base only opens the site for a few hours once or twice a year.

If you look down, below are rocks called Trinitite which were formed from the blast melting and crushing the sand. I picked up a piece, until a nearby soldier told me in no uncertain terms to put it down.

As I walked away, sky displayed an eerie, ominous, uplifting scene, I posted earlier.

Trinitite

The Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, built in 1915 was directly below the blast. All inside, of course, were killed, but the walls did not collapse since the pressure came from above, not the side.

Now called the Atomic Bomb Dome, it is part of the surrounding UNESCO World Heritage Site and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

In the park across the river from the A-Bomb Dome, is the Peace Bell which depicts a world without national borders. The bell was erected in 1964, a similar bell was placed in Oak Ridge, Tennessee in 1993. I have rung both bells.

At one end of the park is the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum displaying artifacts from the bombing and aftermath, and sharing stories of survivors. From a bridge between buildings, you can look over the park. In the image below, you can see the eternal flame. The fire to light the flame was taken from a fire in the Buddhist Shrine on top of Mt. Misen on Miyajima that has burned for over 1,200 years.

Not far from the Trinity Site, is the Los Alamos Laboratory which served as the center of the Manhattan project. Most of the site is still closed to the public, but the home where Robert Oppenheimer lived and other period buildings are part of the National Historic Site you can visit. Of course, the first chain reaction occurred at the University of Chicago, under the football stadium, and you can visit the memorial there. A friend once lived in the former home of Enrico Fermi, and my imagination took me to all the Manhattan Project scientists who must have been in that house.

Shukkieien Garden, Hiroshima

The Shukkeien Garden was created in 1620. Just over a mile from the hypocenter of the blast, it served as a refuge for victims.

A Ginko tree that was toppled in the blast still lives, though this picture was taken before it leafed out for the Spring.